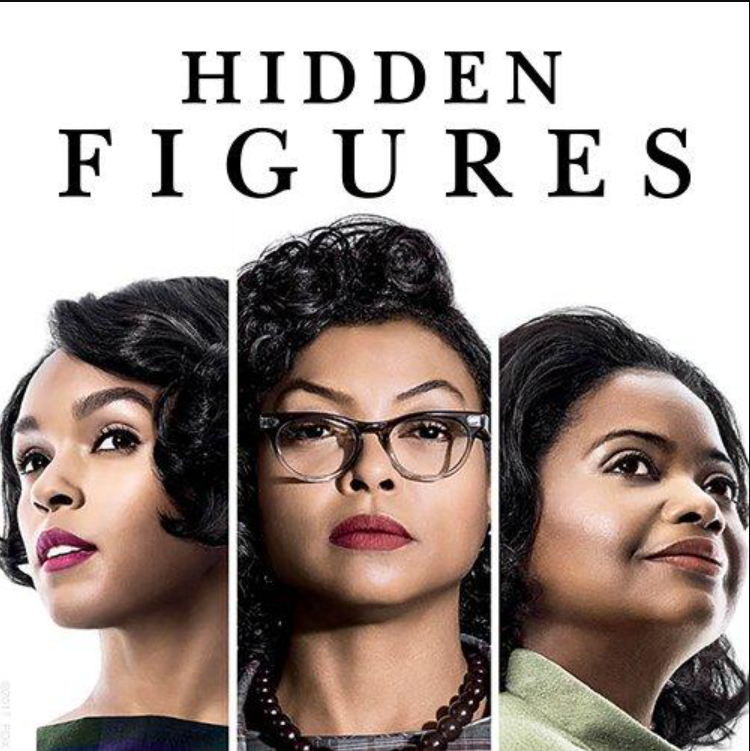

Despite its lifelong presence, my dyslexia diagnosis and accommodations did not come to light until my junior year of high school. My younger self would be pleased that I ultimately got the help I needed, but the elementary years I spent stressing about Friday’s spelling test will not be forgotten. I vividly recall the vacuity I felt when my twin sister would spend minutes studying compared to the hours I needed. Mandatory participation in the county’s spelling bee would prompt a racing heartbeat and an unexcused absence. Reading was a whole other factor. No wonder I procrastinated on the “100 books challenge” in my second-grade class. Looking back, not being able to spell ‘Katherine’ until 5th grade should have been a giveaway.

Once I began high school, I began to notice disparities between me and my classmates. I would take the highest-level classes but still struggle with fundamental concepts. Entering my junior year, I recognized that a change was needed if I wanted to reach my full potential. This prompted my request to be tested for dyslexia. It’s rare for a student to be identified as gifted and talented, along with having dyslexia, but that’s precisely my case.

Early intervention is key to success, but it is not achievable in all cases, including mine. Educators, parents, and oneself play a massive role in diagnosing learning disabilities, so everyone should know the signs and symptoms. The most common symptoms of dyslexia are: poor handwriting, problems processing and understanding what is heard, difficulty finding the right word or forming answers to questions, problems remembering the sequence of things, difficulty seeing (and occasionally hearing) similarities and differences in letters and words, difficulty spelling, spending an unusually long time completing tasks that involve reading or writing, avoiding activities that involve reading, mispronouncing names or words, or problems retrieving words, and difficulty doing math word problems.

More on, years of fog would dissipate once I began a program to help rewire my brain to use strategies instead of resorting to the long way around when reading and writing. I began meeting with a dyslexia specialist, Angie Graham, during my homeroom class period. Sessions would consist of coding sentences and words, practicing pronunciation, and reviewing dozens of flashcards. At the time, it seemed juvenile, but now I can appreciate the neurological stimulation.

I am eternally grateful for the extra support I received. Make it known that anyone dealing with dyslexia or any other learning disability deserves support and the opportunity for equality.

During one class period, my calculus teacher, Mrs. Teresa Kuhn, revealed her dyslexia struggle. I was astonished that the smartest person I knew was also struggling. She routinely speaks about her personal hardship but combats it with her exceptional ability to overcome adversity. Up until she revealed her learning disability, I was ashamed of my brain. I questioned my capabilities and worth. How could I be successful at such a disadvantage? However, understanding that learning disabilities can be overcome changed everything. Without a role model to look up to, my persistence would have been delayed. To reduce shame and ideals of incompetence, conversations around learning disabilities should be normalized.

I encourage anyone experiencing symptoms of dyslexia to reach out and get the help they deserve. Dyslexia isn’t embarrassing; it’s a superpower, as my trainer would joke.

Up until a year ago, no one could persuade me that reading was fun, spelling was not as painful as it seemed, and speaking correctly was easy. But now, everything has changed. The embarrassment I associate with dyslexia and feelings of inadequacy are minimal compared to my real capabilities.